Hi there accounting fans! Let’s calculate FIF tax!

So in the first part to this guide, we discussed the steps to determine if you are eligible for FIF tax. In the second part now, we will look at how to calculate for FIF tax.

The first bit of this part will look at:

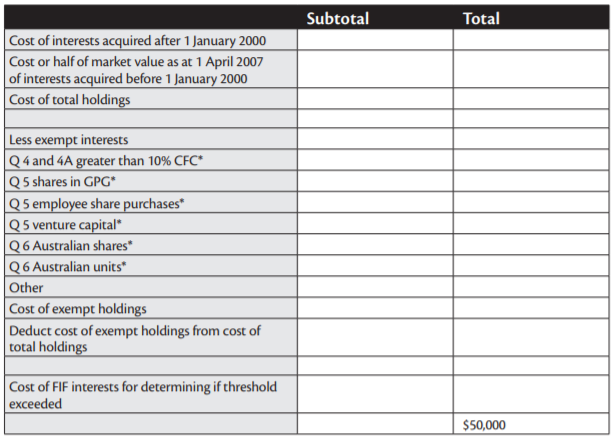

Determining the $50,000 cost to calculate FIF tax

We talked about this briefly in the first part, but now let’s look at greater details how we arrive at the $50,000 cost threshold:

In the first three rows – we have the cost of investments. If all your investments have been acquired after 1 January 2000 (as most of you would have), then you are putting them at full price. Investments purchased before 1 January 2000 can either be put at cost or half of market value as of 1 April 2007. These should include ALL your overseas investments.

The next few rows look at exemptions. This is where we start taking out investments that don’t qualify for FIF tax:

- Investments where you control 10% or more – because these may be taxable under CFC (Control of a foreign company) rules instead

- GPG shares – GPG (Guiness Peat Group plc) is a publicly listed company in the UK. I have no idea why their shares are specifically excluded (perhaps some readers can educate me on that?).

- Employee share purchases – Employee share purchases are share purchases made through an employee share purchase scheme in a foreign company – not all shares acquired this way are exempt though. Check with your accountant for clarification.

- Venture capital are shares bought in start-up companies through a venture capital fund – but these are ONLY for start-ups which were previously NZ resident or have significant NZ business. There is a maximum 10 year exemption for this class of investments. All other foreign venture capital funds fall under FIF rules.

- Australian shares and unit trust funds – as discussed in the first part of this guide, these may be exempt.

Take your total cost, minus total exemptions and you come to the cost for determining if you exceeded the threshold. If it is less than $50,000, you don’t pay FIF tax. Yay. If it is $50,000 or more, you are paying FIF tax. Not so Yay.

How to calculate FIF tax?

Now that we’ve properly established your eligibility for FIF, we move on to the next step, that is calculating the INCOME ATTRIBUTABLE to FIF.

There are several ways of calculating income that you get from your FIF and they are:

- Fair Dividend Rate (FDR)

- Comparative Value (CV)

- Accounting Profits (AP) – unavailable for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2011

- Deemed Rate of Return (DRR)

- Cost Method (CM)

- Branch Equivalent (BE) – unavailable for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2011

- Attributing FIF Income method – available for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2011

WOW that’s a lot of different ways to calculate! Don’t worry. We will only focus on the FDR and CV method for this guide. FDR and CV are the most common methods to determine FIF income.

Fair Dividend Rate (FDR)

5% multiplied by opening market value of your investment at the start of the tax year PLUS quick sale adjustment.

FDR is simple. So simple that it assumes that you’re making income from your FIF every year. For example:

Kiara has $30,000 invested in a Singaporean managed fund. At the beginning of the 2021 tax year, this fund was worth $40,000. She calculates income on her fund using FDR as being $2,000 (5% X $40,000)

Make a quick sale adjustment if you bought and sold and bought again the same investment during the tax year. This is basically 5% X peak holding differential X average cost. You can check out an example on page 19 of the IRD guide.

This calculation is a bit tricky and it is best to get in touch with your accountant if you’re not sure what you’re doing.

Non-portfolio shares cannot use FDR. If this is you, talk to your accountant. However in most cases, FDR is the way to go.

Note that the Cost Method (CM) also uses the same calculation as FDR. CM is for unlisted foreign shares (like shares in a foreign family business) or shares listed on unrecognised stock exchanges.

Comparative Value (CV)

Closing market value + gains MINUS opening market value + costs.

Gains include the growth from holding (including dividends) or disposing of your investment. Costs include the cost of buying the investment plus (if bought during the tax year) foreign income tax and other brokerage/financial fees incurred.

This calculation reflects the actual gain/loss made on your investments. Losses made using the CV calculation can only offset gains from other investment portfolios (including your NZ ones). This loss CANNOT offset income from other types (like employment, or business).

Which method should you use to calculate FIF tax?

In most cases, its either FDR or CV. If you can’t figure out which method to use, FDR is the default method preferred by the IRD. There are certain investments (like a regular individual, non-portfolio share) prohibited from using FDR, in which case you should use CV. Please note that CV is ONLY applicable if you are a natural person or family trust. If you are paying FIF tax under your company, you can only choose FDR.

From a tax perspective, its better to go with CV, as you may overstate your actual income on FIF using FDR. FDR may be better in years where you make a HUGE gain on your foreign investments which is more than 5% of your opening market value. If you have a choice between CV and FDR – you CANNOT claim losses on your CV. If you have no choice but to use CV, you can claim losses on the investment (like if your individual share you invested in reduced in value over the tax year)

Let’s look at an example of FDR compared with CV:

Charlie holds investments in three foreign companies. The following table shows the details of his investments:

| Company name | Opening Market Value | Closing Market Value | FDR income | CV Income |

| Pear Inc. | $300,000 | $250,000 | $15,000 | -$50,000 |

| Hand Book | $100,000 | $120,000 | $5,000 | $20,000 |

| Macrohard | $200,000 | $205,000 | $10,000 | $5,000 |

In the example above, under FDR, Charlie declares a total income of $30,000 under FDR but a loss of $25,000 under CV. Naturally, Charlie would opt for the CV method because it allows him to declare zero income from his FIF for the financial year. Remember – any loss on FIF can only be used to offset income from other portfolios. So if Charlie made income of $40,000 from his NZ funds, he can use the $25,000 loss under CV to reduce his total investment income to $15,000. If Charlie made less than $25,000 income from his NZ funds, he declares zero income for his total investment income since his FIF loss would take him below zero.

Each financial year, you can choose which calculation method you want to use. Once you’ve chosen one calculation method you MUST use the same method across ALL investments and you CANNOT change the method in the middle of the financial year.

Foreign tax credits

But wait! We’re not done yet! If you’ve been investing in FIF, there is a good chance that your FIF has been taxed in its local country. If this country has a Double-Taxation Agreement (DTA) with NZ, you can claim back those foreign tax credits! There is a limit on how much tax credits you can claim. This is calculated based on your notional tax per investment segment. The actual calculation of this is quite complicated and I highly recommend talking to your accountant to sort this out.

If you want to, you can take a look at the policy guide page 27-28 for more information on how to do this yourself.

Paying tax on your FIF

Simply add the FIF income (either FDR or CV) to your NZ investment income, and you get your total investment income.

This total investment income is added to your total taxable income and you are taxed on a scale rate based on that. For example:

Bruni has received $40,000 income from employed work. They have investment income from NZ funds of $10,000. Bruni also has foreign investments and using FDR, their income from overseas was $5,000. There were $500 worth of foreign tax credit they could claim. Their total investment income would be ($10,000 + $5,000 = $15,000). Add this to their employment income of $40,000. So their total income is $40,000 + $15,000 = $55,000. This $55,000 is Bruni’s taxable income. Assuming an average tax rate of 12.5%, Bruni will pay taxes of $6,875.

From $6,875, Bruni can offset it with the foreign tax credits of $500, PAYE tax credits and tax paid at source on their NZ fund income. Assuming PAYE tax credits of $5,000 and tax credits on NZ funds of $1,200, Bruni ends up with a tax payable of $175.

Once again, remember that if you make a loss on your investments, it CANNOT offset income from other sources!

Phewh!

And that’s how you calculate FIF tax!

Well, that was quite a read! FIF tax is certainly not the most simple tax to figure out, but I hope that this guide has proven useful to you. This guide is most useful if you only hold foreign shares/unit trusts. If you hold other types of investments, get in touch with me at sam@samharith.com for more personalised advice.

In the meantime,

Stay positive!