(tax splitting – 5 minute read)

Hi there accounting fans!

Hot on the heels of our last article on Shareholder Salaries, this time we are going to talk about income tax splitting for companies!

Remember how with shareholder salaries, you can effectively split the income between your company and yourself as an individual. This means that instead of paying tax on a $100,000 profit through your company at 28%, you can pay yourself say, $80,000 of that amount. Then, keep the remaining $20,000 in the company. This means that $80,000 taxed in your name is taxed at the personal tax rate, and the balance $20,000 is taxed at a company rate of 28%.

If you have multiple shareholders who work for the business, you can further split the income earned by the company towards each individual shareholder.

Tax splitting is pretty cool. It’s also a popular tool among accountants to help plan taxes for their clients. But before we talk more about tax splitting, let’s get one thing clear:

Don’t commit tax avoidance with tax splitting

By splitting income from a company to its shareholders, you are effectively taking advantage of lower personal income tax rates.

Let’s revise:

Company tax rate in NZ = 28%

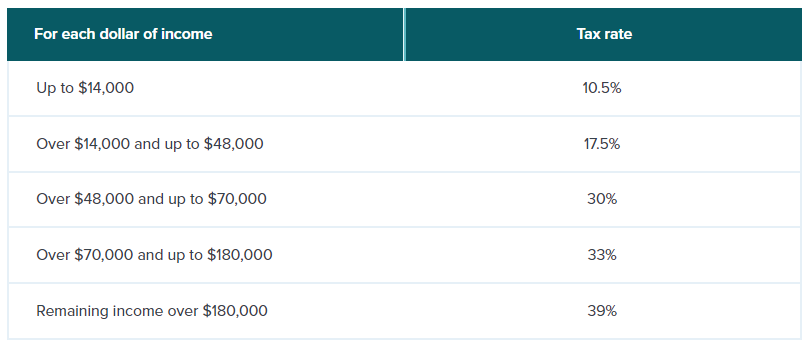

Personal tax rate = A variable scale rate that looks like this:

Let’s illustrate this with an example:

Yubble Ltd makes a profit of $60,000 for the year. If profits were declared through Yubble Ltd, they would be looking at a tax bill of $16,800.

Ouch. $16,800 (28% of $60,000) is a lot. Let’s see what happens if they paid their shareholders a shareholder salary:

Yubble Ltd has two shareholders who work in the business, Yub and Bubble. At the end of the financial year, they agree that they both contributed equally to the business and that they would pay shareholder salary of $30,000 each.

So instead of taxing that whole $60,000 in the company’s name, Yub and Bubble are now paying taxes on income of $30,000 each at their personal tax rate. This means each shareholder is paying about $4,270 each (an effective tax rate of 14.2%). In total, they are looking at a tax bill of $8,540 ($4,270 times two shareholders).

As you can see, $8,540 is a lot less than $16,800 (almost half as less).

Now if there was a third shareholder who was working in the business, they could theoretically split the $60,000 even further, with each shareholder getting $20,000 each. At $20,000, that is tax of only $2,520 for each shareholder (an effective tax rate of 12.6%) which means the total tax bill is $7,560 ($2,520 times three shareholders).

In other words, the more you split the income, the lower your overall tax bills become. As you can imagine, this does create conditions ripe for tax avoidance – which is a big NO-NO.

To avoid being pegged for tax avoidance, here is what to do:

Only do tax splitting for shareholders who work for the company

This one is important.

When paying out shareholder salary, you MUST ONLY PAY shareholders who have contributed to the running of the business. If you have sleeping shareholders (shareholders who only invest, but don’t work in the business) you can’t pay them a shareholder salary.

Remember that shareholders salary is compensation paid to shareholders who have worked in the business. Paying shareholders who don’t work in the business is tax avoidance and will get you in trouble.

You can still pay investing shareholders a dividend. But dividends are taxed 33% at source so you’re not going to get any tax benefit from doing so.

Pay your shareholders a market rate

Shareholders must be paid a market rate or close to market rate for their services.

You can’t be sneaky and pay yourself as a shareholder $48,000 to avoid the 30% tax bracket and keep the balance in the company accounts to be paid at 28%. Don’t do it. It’s wrong. That’s tax avoidance.

You should know what your market rate is for your work. This is the salary that you would get paid annually if you were performing your work as an employee for a different company.

Remember that when it comes to paying shareholder salaries, you can’t pay more than what’s left in the company’s profit for the year. This means that if you have only $50,000 left in profits but your market rate is $60,000, you can only pay yourself a maximum of $50,000 for shareholder salary.

Tax splitting equally or based on contribution to work

This one is a bit more tricky.

The general advice I give to clients is to split their income equally between the different shareholders in the business, provided that they all are working for the business.

Sometimes one shareholder works more than the others. In this case, the shareholders could distribute shareholder salary based on their level of contribution to the company. As you can imagine, this can be quite tricky (and controversial, if shareholders disagree about how much each of them has put into the business).

To keep it simple, just go for an equal split.

Other things you need to know about tax splitting

If one of your shareholders has a full-time job or income from other sources, you may opt to pay them a lower shareholder salary. This makes practical sense because their contribution to the business would only be on a part-time basis. From a tax point of view, they wouldn’t be declaring too much income in their name which keeps their income from going to the higher tax brackets. In this case shareholders who work full-time in the business can get paid a larger shareholder salary.

The same goes for businesses where the spouses are shareholders. One spouse could have a full-time job which is high paying and only does business work part-time. In this case it’s more practical to ONLY pay the full-time shareholder spouse shareholder salary. By splitting the income in this situation, the spouse with the full time job could end up paying tax at a higher bracket.

Tax splitting with other entities

In Aotearoa NZ, the three most popular entities for tax splitting are companies,partnerships and trusts. This article has only discussed tax splitting from a company perspective.

Partnerships don’t have shareholder salaries but instead, income is distributed based on an agreed % between the partners to each partner’s invidual income. There is no option to retain the profits in the partnership as partnerships don’t pay taxes. Only their partners pay taxes in their individual names (based on the partnership income distribution).

Trusts are very different from companies and partnerships in that you can split trust income to beneficiaries who are above the age of 16. But there are also other considerations when managing a trust which can affect tax splitting. Also, trusts are, in my opinion, an inefficient structure from which to run a business (but more on that in a future article).

For now, this article should have provided a good overview of how tax splitting works for companies in Aotearoa NZ. This should also help business owners who are looking at achieving tax efficiency while recognising the contributions of their shareholders WITHOUT committing tax avoidance.

So yes, tax splitting is cool – but you must use it correctly!

Stay positive!